I’ve never much liked Superman.

I’ve never much liked Superman.

Although Smallville did a decent job of injecting the man of steel with a touch of humanity, the character as a whole is overburdened by his squeaky clean, unambiguous morality.

I like my heroes to struggle with their call to action. I want them to come kicking and screaming into the light. Don’t give me Mr. Saintly who saves the day because it’s the right thing to do. Give me a guy who saves Earth because it’s got the best pizza in the universe and, oh, yeah, his friends, all two of them, happen to call the little blue rock home.

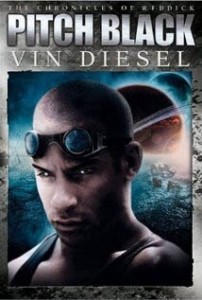

Which is why Pitch Black is one of my favorite movies. Not only is the hero as dark as the movie’s title, but the supporting cast also has a furious case of flexible ethics.

Riddick (Vin Diesel), the film’s hero, is about as “anti” as an anti-hero can get. He’s spent so many years incarcerated in the deepest, darkest prison in the universe, that he’s had his eyes modified to see in the dark. He doesn’t just ignore his call to heroism; he’s stopped paying the phone bill, and moved out of town leaving no forwarding address.

The film begins with Riddick’s narration, as he explains that he’s on a ship in deep space, headed for prison (after another escape), escorted by lawman William Johns (Cole Hauser). Riddick is unapologetic about his detachment from the rest of the human race, observing that, “They say most of your brain shuts down during cryo-sleep. All but the primitive side, the animal side. No wonder I’m still awake.” He goes on to give a quick, prescient rundown of the rest of the cast, his assumptions of profession and destination based solely on their scent. The rest of his companions in cryo-sleep are a mixture of settlers, miners and pilgrims.

Then the ship is peppered by a meteor shower that tears through the hull like shrapnel, damaging crucial systems and killing the captain. The remaining crew, a navigator and the docking pilot, Carolyn Fry (Radha Mitchell) struggle to land the ship as it plummets into the atmosphere of a nearby planet.

The awkward, rectangular ship is careening down, its nose pointed up. For Fry, the choice is clear. Dump the cargo, else no one–particularly her–will survive. “I’m not dying for them,” she says and pulls the level to disengage the section of the ship that carries the passengers, e.g., the cargo. Except the navigator stops her, wedging something between the door to the cargo area and the front of the ship.

His actions, though noble, are largely, pointless. The majority of the ship’s rear end is strewn across the planet’s arid surface. Amusingly, the few surviving passengers quickly declare Fry the hero for having saved them from death. This positions Fry as The Hero Who Isn’t, as opposed to Riddick, who is reviled by all right from the start. Of course, you know, at some point, the survivors will learn that Fry was all too happy to jettison their cryo-snoozing asses into space to save her own. And Riddick will eventually save the day. (Well, sort of.)

The principle character dynamic lies between Riddick, Fry, and Riddick’s “handler,” William Johns, a man with his own share of secrets. This “he/she isn’t what he/she appears to be” plotline between the trio is the movie’s strength.

The basic idea is the stuff that all horror films are made of: trapped somewhere, surrounded by monsters. In this case, it’s hungry, light-phobic beasties, who, thanks to a lengthy solar eclipse, now have a pitch black planet-size hunting ground. The monsters, when revealed, are scary enough; there’s a smattering of gore; and ample suspense. But Pitch Black distinguishes itself with its complex character interactions.

The thing about anti-heroes, deeply flawed characters, and for that matter, interesting villains, is that quite often they have a point. Fry’s decision to rid the ship of extra weight is sound. It’s not nice, but it’s really the only logical thing to do. Similarly, Riddick’s deeply cynical view of humans– “I truly don’t know what’s gonna happen when the lights go out, Carolyn, but I do know, once the dying starts, this little psycho fuck family of ours is gonna rip itself apart” –is dead on. When the poop starts flying, the survivors do turn on each other.

Anti-heroes get to say what we are all thinking. (Which is why they are deliciously fun to write.) They reveal the ugly truths lurking behind the false civility. In particular, the fact that most of us take care of “Me and my own,” to quote Malcolm Reynolds, another great anti-hero.

We’d all like to think we’d run into the burning building to save a dozen total strangers. Most of us, self included, would take one look at the inferno, and call 911, letting the firefighters risk their bacon. Anti-heroes are rarely motivated, at least initially, by the greater good. Like us, anti-heroes don’t step up until someone they care about is at risk. In the process, they may save an entire planet of cute fuzzy-wuzzies from the evil overlord, but their primary motivation was to protect, Bob, their favorite fuzzy-wuzzy, the rest of the little hairy fuckers be damned.

Riddick’s transformation to hero is geologically slow, his primary motivations apparently staying alive (like everyone else), and possible gaining the upper hand. His fuzzy wuzzy is Fry, in whom he initially sees a kindred soul. After all, she was ready to space him and the rest of the civilians to save herself, and above all else, Riddick respects a strong survival instinct. Fry, meanwhile, isn’t a stone cold killer, but a human being who made a hard decision under extreme duress. While Riddick is the obvious protagonist in the story, Pitch Black is also Fry’s story. Basically, Riddick and Fry are on parallel redemption paths. One grudgingly at best, the other pursuing redemption with tremendous tenacity.

Another, plus, Pitch Black isn’t the usual testosterone-poisoned action spectacle. Though the cast of Pitch Black is male-dominated, the three female characters aren’t damsels in distress, and there is little in the way of gratuitous fan service for the male audience. With one interesting exception, gender is never really an issue. By and large, the survivors, including Riddick, accept Fry as the defacto leader, only challenging her when things start to go really bad.

Pitch Black is one of the best SF horror flicks since Aliens. Recommended.